由斯蒂芬·菲德斯

我不断认为那些真正伟大的人。

从子宫中,谁记得灵魂的历史

通过光的走廊,时间是太阳,

无穷无尽。谁的可爱雄心壮志

是他们的嘴唇,仍然被火,

应该讲述精神,从头到脚穿上歌曲。

谁从春天的分支囤积了

欲望落在他们的身体上就像开花一样。

什么是珍贵的,永远不会忘记

从agoust弹簧绘制的血液的基本喜悦

在我们的地球面前穿过世界的岩石。

从来没有否认在早晨的乐趣简单的光线

对爱情的严重需求也不。

永远不要逐渐交通窒息

用噪音和雾,精神开花。

在雪附近,在阳光下,在最高的领域,

看看这些名称如何被挥舞着的草

并且是白云的飘带

在听力的天空中的风声。

那些在生活中的人的名字为生而战,

谁在他们的心中穿着火的中心。

他们出生的阳光,他们走向太阳

并留下了荣誉的生动空气。

斯蒂芬·菲德斯,“真正的伟大”来自收集1928-1953。版权所有©1955由Stephen Spender。通过ED Victor Ltd.许可转载

来源:收集1928-1953(Quary House Inc.,1955)

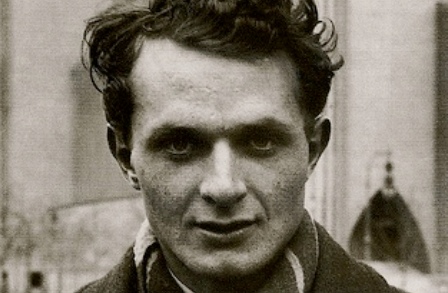

诗人生物

诗人和评论家斯蒂芬斯·菲德斯出生于1909年在伦敦。他是在20世纪30年代突出的英国诗人的一代人的成员,其中一群人有时被称为牛津诗人 - 包括W.H.奥登,克里斯托弗·伊瑟林,C。刘易斯和路易斯·麦克斯伍德。在芝加哥论坛教堂世界的一篇关于斯宾德的作品中,杰拉德·尼科西亚写道:“在为传统价值观和高标准的工艺保持敬意,而且[这些诗人]转过身来源于T.S.艾略特,坚持认为作者与当天的紧急政治问题保持联系,他以声明的声音说明的声音。“斯宾德的众多诗歌包括海豚(1994),收集的诗歌,1928-1985,慷慨的日子(1971年),奉献诗(1946年)和仍然中心(1939年)。在第二次世界大战期间,担保人为伦敦消防局致力于伦敦消防局。从1965年到1966年,他担任诗歌顾问到国会图书馆。1970年至1977年,伦敦大学学院英语教授,他经常在美国大学讲课。他在1983年被们骑士。士班的名字最常与W.H.的名字有关。 Auden, perhaps the most famous poet of the 1930s. However, some critics, including Alfred Kazin and Helen Vendler, found the two poets dissimilar in many ways. In the New Yorker, for example, Vendler observed that “at first [Spender] imitated Auden’s self-possessed ironies, his determined use of technological objects. … But no two poets can have been more different. Auden’s rigid, brilliant, peremptory, categorizing, allegorical mind demanded forms altogether different from Spender’s dreamy, liquid, guilty, hovering sensibility. Auden is a poet of firmly historical time, Spender of timeless nostalgic space.” In the New York Times Book Review Kazin similarly concluded that Spender “was mistakenly identified with Auden. Although they were virtual opposites in personality and in the direction of their talents, they became famous at the same time as ‘pylon poets’—among the first to put England’s gritty industrial landscape of the 1930s into poetry.” The term “pylon poets” refers to “The Pylons,” a poem by Spender that many critics described as typical of the Auden generation. The much-anthologized work, included in one of Spender’s earliest collections, Poems (1933), as well as in his Collected Poems, 1928-1985, includes imagery characteristic of the group’s style and reflects the political and social concerns of its members. In The Angry Young Men of the Thirties (1976), Elton Edward Smith recognized that in such a poem, “the poet, instead of closing his eyes to the hideous steel towers of a rural electrification system and concentrating on the soft green fields, glorifies the pylons and grants to them the future. And the nonhuman structure proves to be of the very highest social value, for rural electrification programs help create a new world of human equality.” The 1930s were marked by turbulent events that would shape the course of history: the worldwide economic depression, the Spanish Civil War, and the beginnings of World War II. Seeing the established world crumbling around them, the writers of the period sought to create a new reality to replace the old, which, in their minds, had become obsolete. For a time, Spender, like many young intellectuals of the era, was a member of the communist party. “Spender believed,” Smith noted, “that communism offered the only workable analysis and solution of complex world problems, that it was sure eventually to win, and that for significance and relevance the artist must somehow link his art to the Communist diagnosis.” Smith described Spender’s poem, “The Funeral” (included in Collected Poems: 1928-1953, published in 1955, but omitted from the 1985 revision of the same work), as “a Communist elegy.” Smith observed that much of Spender’s other works from the same early period—including his play, Trial of a Judge: A Tragedy in Five Acts (1938), his poems in Vienna (1934), and his essays in The Destructive Element: A Study of Modern Writers and Beliefs (1935) and Forward from Liberalism (1935)—address communism. In Poets of the Thirties, D.E.S. Maxwell commented, “the imaginative writing of the thirties created an unusual milieu of urban squalor and political intrigue. This kind of statement—a suggestion of decay producing violence and leading to change—as much as any absolute and unanimous political partisanship gave this poetry its marxist reputation. Communism and ‘the communist’ (a poster-type stock figure) were frequently invoked.” The attitudes Spender developed in the 1930s continued to influence him throughout his life. As Peter Stansky pointed out in the New Republic, “The 1930s were a shaping time for Spender, casting a long shadow over all that came after. … It would seem that the rest of his life, even more than he may realize, has been a matter of coming to terms with the 1930s, and the conflicting claims of literature and politics as he knew them in that decade of achievement, fame, and disillusion.” Spender continued to write poetry throughout his life, but it came to consume less of his literary output in later years than it did in the 1930s and 1940s. Critics praised his work as an autobiographer and critic. In a Times Literary Supplement review, Julian Symons noted “the candor of the ceaseless critical self-examination [Spender] has conducted for more than half a century in autobiography, journals, criticism, poems.” Stansky believed that Spender was at his best when he was writing autobiography. The poet himself pointed echoed this assertion in the postscript to The Thirties and After: Poetry, Politics, People, 1933-1970 (1978): “I myself am, it is only too clear, an autobiographer. Autobiography provides the line of continuity in my work. I am not someone who can shed or disclaim his past.” In the 1980s, Spender’s writing—The Journals of Stephen Spender, 1939-1983, Collected Poems, 1928-1985, and Letters to Christopher: Stephen Spender’s Letters to Christopher Isherwood, 1929-1939, in particular—placed a special emphasis on autobiographical material. In the New York Times Book Review, critic Samuel Hynes commented that “the person who emerges from [Spender’s] letters is neither a madman nor a fool, but an honest, intelligent, troubled young man, groping toward maturity in a troubled time. And the author of the journals is something more; he is a writer of sensitivity and power.” One of Spender’s earliest published works of autobiography, World within World (1951), created a stir due to Spender’s frank disclosure of a queer relationship he had had at around the time of the Spanish Civil War. In 1990s, the book became the subject of a controversy when American writer David Leavitt published While England Sleeps (1993). In this novel, many details in the portrayal of a character’s affair mirror experiences Spender shared in his autobiography. Spender accused Leavitt of plagiarism and filed a lawsuit in British courts to stop the British publication of the book. In 1994, Leavitt and his publisher, Viking Penguin, agreed to a settlement that would withdraw the book from publication; Leavitt made changes to While England Sleeps for a revised edition. During this period of intense attention focused on World within World, St. Martin’s reprinted the autobiography with a new introduction by Spender. As a result, many readers had the opportunity to discover or rediscover Spender’s work. “With the passage of time,” commented Eric Pace in a New York Times obituary, “World within World has proved to be in many ways Sir Stephen’s most enduring prose work because it gives the reader revealing glimpses of its author, Auden and Mr. Isherwood and of what it was like to be a British poet in the 1930s.” Spender died in 1995.通过这个诗人查看更多

更多关于艺术与科学的诗

emily dickinson在诗歌猛烈

我会告诉你为什么她很少从她的房子里冒险。

它发生这样的事情:

有一天,她乘坐火车去波士顿,

让她走向黑暗的房间,

把她的名字放在法学剧本中

并等待她的转弯。

当他们读她的名字......

在面具下太多年后改变了

我能感觉得出你

......

关于生活的更多诗

emily dickinson在诗歌猛烈

我会告诉你为什么她很少从她的房子里冒险。

它发生这样的事情:

有一天,她乘坐火车去波士顿,

让她走向黑暗的房间,

把她的名字放在法学剧本中

并等待她的转弯。

当他们读她的名字......

在面具下太多年后改变了

我能感觉得出你

......

关于大自然的诗歌

对于遗骸的野生辉煌

有时我会紧张

......

在面具下太多年后改变了

我能感觉得出你

......